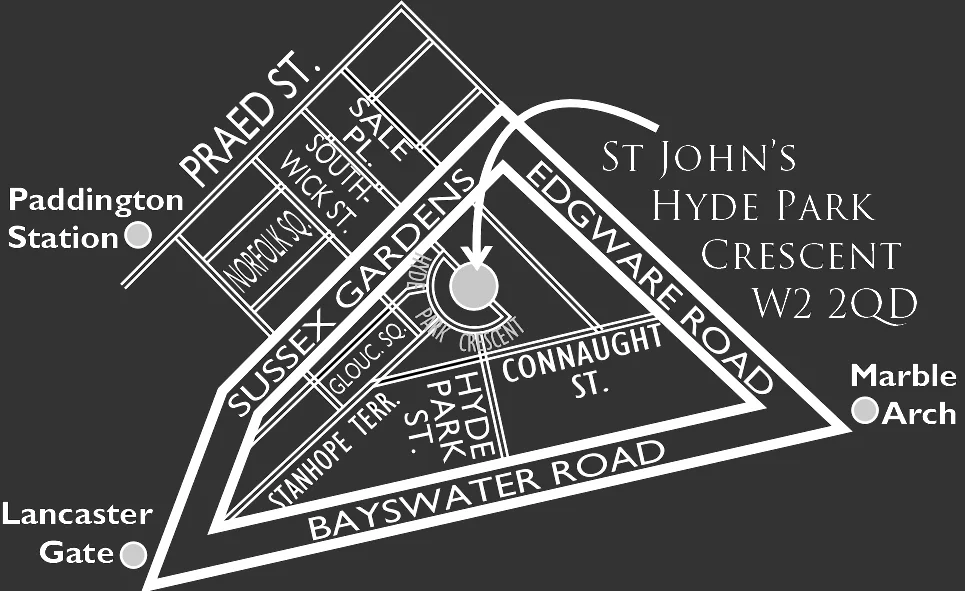

St John's describes itself as an 'Inclusive' church with a diverse community. But, What is Inclusivism and what has it got to do with Christianity and St John’s?

Of course, “Inclusivism” isn’t really a word -no spell check will recognise it. And anyway, our secular post-modern post-Christian culture already considers itself inclusive: of religion, of gender, of sexuality. It prides itself in being tolerant and open-minded, and liberated from ways of thinking that have led to the oppression of minority groups in the past.

Inclusivity has its roots in the Enlightenment and a growing awareness that possessing objective truth was not as simple as previous generations had thought. The philosopher Kant, in trying to solve an impasse in 18th century philosophy, pioneered an approach that has its final expression in the relativism of our present day. He said that we can not know things as they really are in themselves, only as they appear to us; there is Truth, but we cannot know what it is.

This approach to reality has left the Church harassed. After all, Christianity claims knowledge of the Truth: that is, of the saving will of God made known through the person of Jesus Christ. In response, its members have taken many different routes. Some Christians have re-interpreted Holy Scripture, and found in the Bible an unerring source of objective truth. God’s revelation is absolute and unchanging, and this provides a great deal of certainty in an uncertain world. In its extreme form this approach can deny modern science and embraces ideas such as creationism.

Other Christians have evolved with the times, taking on board scientific discoveries, psychological theories, philosophical reflections and the experience of living with other cultures. An Inclusivist approach is one which rejoices in being a child of its time because it believes God rejoices in our time too. We do not live or think in a vacuum and we cannot deny the intellectual advances of our own age.

In this respect, Inclusivism is also fully rooted in scripture. Rather than believing the Bible to be just a book of true propositions about God recorded by different writers, it is seen as the record of humankind’s search for God and the evolution of our awareness and knowledge of Him. In fact, scripture describes a two way process between God and humanity—the history of our relationship with God.

The concept of God develops theologically within scriptural history. For instance, within the Hebrew Scriptures (the Old Testament) we can trace the development of the people of Israel. They changed over time from a nomadic to an agrarian people. Later still they developed into City dwellers whose cultic worship revolved around the temple in Jerusalem. As they became a more complex people so their concept of God developed accordingly, and this should not surprise us.

Insights into the divine nature are overlaid and underlaid with cultural and social anomalies. Thus, an Inclusivist does not reject homosexuality just because of a handful of passages from the Jewish Law and the Letters of the New Testament which attack particular practices within a particular culture. Rather, we find in the Bible an overwhelming message about God’s love for us and how we are to love one another. We rejoice with God when we find people embodying that love in their lives. We recognise that the Biblical writers did not live in our society and did not know what we know about human sexuality and gender. We find God’s grace in the acceptance of people, not in their exclusion.

Theologically, Inclusivism contains a position taken on the world religions. Rather than holding that only those who accept Christ are saved, it recognises that other religious traditions can mediate God’s grace. In Jesus, God brings redemption for the whole of creation and humankind. The gift of the incarnation, ministry and sacrifice of Jesus cannot be curtailed: it is God’s gift to the whole of humanity. This is not saying that all religions are equal, but that the God of grace can be known through Islam, Hinduism, Judaism and other faiths. We would argue that, since God wants all humanity saved, salvation must be available outside the church; after all, many people today and in the past have not heard the gospel. Karl Rahner has called such people ‘anonymous Christians’.

Naturally there are theological problems. How can salvation be found in the other faiths if we wish, at the same time, to argue for redemption being an historical as well as a spiritual event found in Jesus Christ? Aquinas and subsequent writers such as C S Lewis have spoken of a moral law written into the universe (in much the same way as there are physical laws) to which all people are bound. This exists outside of revelation. A devout Muslim who obeys the moral law is blessed by God.

Others look to the Trinity. If the Three Persons of God are all equal, then someone who worships the Father ‘in spirit and in truth’ (a Muslim or Jew for example) is thereby also worshipping the Son, just as a Christian is worshiping the Father through obedience and dedication to the Son.

Over the centuries, the Church has supported many things which it would not support today. The history of slavery, and the life stories of those denied justice because they were women, poor, disabled or not white provide many examples. Yet at the same time Christianity has been a great engine for social change in the world, responding to the needs of the persecuted, the poor and those pushed to the margins of society. Very often the Church has been at the forefront of movements for social change, and this continues in our own day with organisations like Jubilee 2000. To be a Christian today means to be alive to that history, and to actively combat injustice, following the example of Christ given to us in the Gospels to love and care for those in need.

Inclusivism calls Christians to live out God’s grace in their lives through their acceptance of other people. Their creed, sexuality, gender or background do not matter. It leaves judgement to God, and seeks to offer a renewed understanding of the redemptive love of God which changes lives and gives hope to all people.